Last week, I referred to a Financial Times opinion piece by Simon Kuper about language learning, entitled “Learning another language? Don’t bother”.

Last week, I referred to a Financial Times opinion piece by Simon Kuper about language learning, entitled “Learning another language? Don’t bother”.

The article makes the point that, for native speakers of English in today’s world, there is little reason to learn a second language. With the rest of the world mastering English at acceptable levels, and with the advancement of smartphone apps that translate on the spot, the writer opines that the costs of language study probably outweigh the benefits.

Reading the article made me curious enough to purchase one of the books cited therein, William Alexander’s memoir Flirting with French: How a Language Charmed Me, Seduced Me, and Nearly Broke My Heart. In this recently published work, Alexander describes a mighty personal challenge that began for him at age 57, when he decided to fulfill his lifelong dream of learning French.

It turns out that Alexander is more than your average Francophile. He says that he would like to be French, and so he sets out on a 13-month full-time quest to conquer the language he loves. His program includes constantly watching French television, five levels of Rosetta Stone, several audio courses, hundreds of podcasts, numerous dual-language books, 52 TV episodes of French in Action, two immersion classes, and regular emailing or Skyping with French pen pals.

Does he succeed in becoming fluent? From his account of his final week in immersion, one would think not. As he writes, by Thursday, “my lips sore from vowels and my throat raw from searching (in vain) for the letter r, the fog of French has descended heavily over my brain.” On the other hand, and as we will see further on, studying French may have had a far greater impact on his life than actually learning to speak it ever would.

By coincidence, I also read last week a blog post by Salman Khan, the celebrated founder of Khan Academy: In this article, Khan argues that the brain actually grows by struggling with things that are difficult for it to learn. As an example, he recounts the reading adventure he is currently sharing with his young son:

“My 5-year-old son has just started reading. Every night, we lie on his bed and he reads a short book to me. Inevitably, he’ll hit a word that he has trouble with: last night the word was “gratefully.” He eventually got it after a fairly painful minute. He then said, “Dad, aren’t you glad how I struggled with that word? I think I could feel my brain growing.” I smiled: my son was now verbalizing the tell-tale signs of a “growth mindset.” But this wasn’t by accident. Recently, I put into practice research I had been reading about for the past few years: I decided to praise my son not when he succeeded at things he was already good at, but when he persevered with things that he found difficult. I stressed to him that by struggling, your brain grows. Between the deep body of research on the field of learning mindsets and this personal experience with my son, I am more convinced than ever that mindsets toward learning could matter more than anything else we teach.

“Researchers have known for some time that the brain is like a muscle; that the more you use it, the more it grows. They’ve found that neural connections form and deepen most when we make mistakes doing difficult tasks rather than repeatedly having success with easy ones.

“What this means is that our intelligence is not fixed, and the best way that we can grow our intelligence is to embrace tasks where we might struggle and fail.”

When I read Khan’s piece, it confirmed and helped advance some of my recent thinking about learning in general, particularly about teaching children. And, it caused me to think back to Alexander’s efforts at learning French. In fact, the growth mindset that helps the 5-year-old increase his mental capacities seems to work also for adults. After struggling with French for little more than a year, Alexander discovered a hidden benefit, one “so startling, so important, I can almost overlook my failure to learn French”.

After his year-long French immersion experience, Alexander re-took a cognitive-functioning test that he taken the previous year. He was amazed to find that his scores had skyrocketed. Next week, I will discuss some of the implications of Alexander’s discovery, of language learning in general, and how it may help us in our quest to become better at systems thinking.

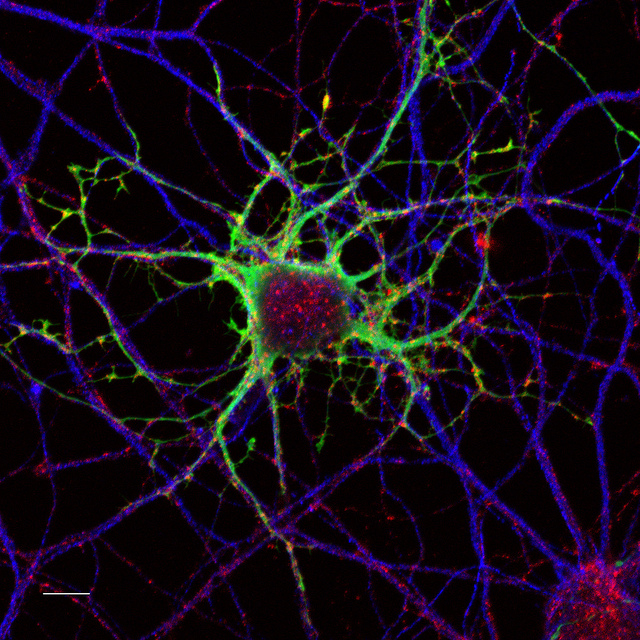

Image: Flickr-user ZEISS microscopy

1 Comment

-

This is exactly why I believe immersion programs should be the status quo in elementary schools. In Canada, that would be French Immersion. From the first day of school, the brains of children in a language immersion program are put brain through an exercise routine that would be difficult match in a first language setting. Add to the immersion program a third language and instrumental music, and schools would really be providing a “boot camp” for brains.