In the next two posts, my plan is to highlight several concepts from recent entries, and review them through the lens of a single example. In particular, there are three points I would like to emphasize:

In the next two posts, my plan is to highlight several concepts from recent entries, and review them through the lens of a single example. In particular, there are three points I would like to emphasize:

1. how the act of story telling helps the teller evolve, both as a speaker and as a leader

2. the valuable benefits of audience interaction

3. the role that happenstance can play in an orator’s development

For today, I will address the first of these questions, how the simple act of telling can help the teller evolve. Next time, we will take a look at the other two.

One of the most fascinating things I have learned in my career, both from studying leaders and from helping my clients influence their worlds, is what happens when people learn to speak from the heart and tell their personal stories of identity. As they shape their stories of “who I am” or “why I do things the way I do”, these stories will in turn be shaping them.

In fact, I have witnessed dramatic changes in a significant number of the people I have worked with, those who have made authentic personal stories a central element of their speaking. Many have bolstered their self-confidence, challenged themselves to reach new heights, even redefined themselves, with the help of the stories of self they come to believe, and the ways they learn to share these personal narratives with others.

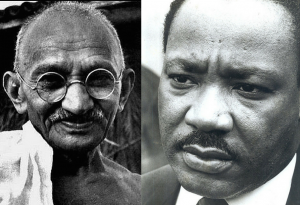

Speaking from the heart through the vehicle of our personal stories is indeed a very powerful tool. It is undoubtedly the best means sharing what truly matters to us. This act of sharing can deepen our self-knowledge, strengthen our conviction, and help us grow. In this vein, the experience of Martin Luther King is once again enlightening.

Dr King is clearly a fine example of someone whose telling of personal stories of identity solidified his beliefs, and eventually gave him the confidence to reach out to a broader public. His sphere of influence would expand dramatically, along with his desire to speak to the world.

As we have seen briefly in previous posts, Martin Luther King was already a competent orator as a young pastor in 1955, but someone who had little desire for leadership roles on a national, or even a regional, stage. His powerful voice—and his deep convictions regarding nonviolence and reaching out to those of all races and faiths—were elements that evolved over time with the stories of identity he told.

Dr King’s watershed moment—the event that would cause his story to grow and bring him to national prominence—came when he was chosen as a leader and spokesperson for the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Both with his audiences and in smaller groups during the boycott, he often made reference to his years of academic and theological training. His study of all the world’s religions gave him a humanistic bent, which he pointed to as his fundamental reason for advocating inclusion. Their protest in Montgomery, Dr King advised, should not only be about mobilizing blacks and their churches. To be truly successful, the movement would also have to appeal to whites, and to gather support from people of all faiths.

When radical voices called for violent civil disobedience in Montgomery, Dr King countered by speaking of his deep admiration for Mohandas Gandhi’s precepts of nonviolence. Combining inclusion and nonviolence would in the end allow him to keep much of mainstream America—both black and white—on his side.

In the end, telling why Gandhi’s philosophy was so important to him personally would cause this story to grow, and the teller himself would increase his confidence in, and commitment to, a strategy of nonviolence and inclusion. In other words, the tale he told of Gandhi helped Dr King himself grow into a larger story.

Gandhi’s story would indeed become an integral part of Dr King’s identity. As the events in Montgomery unfolded, Reverend King referred all the more often to India’s Mahatma Gandhi as ‘‘the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change’’.

After the success of the boycott in 1956, King’s respect for Gandhi’s thinking led him to contemplate traveling to India to deepen his understanding of Gandhian philosophy and principles. When he eventually arranged for a five-week visit in 1959, Dr King made a comment upon arrival that demonstrated how much Gandhi and India were evolving into an essential part of his stories of identity: ‘‘To other countries I may go as a tourist, but to India I come as a pilgrim.’’

Image: Flickr-users U.S. Embassy New Delhi and Francesca Romana Correale