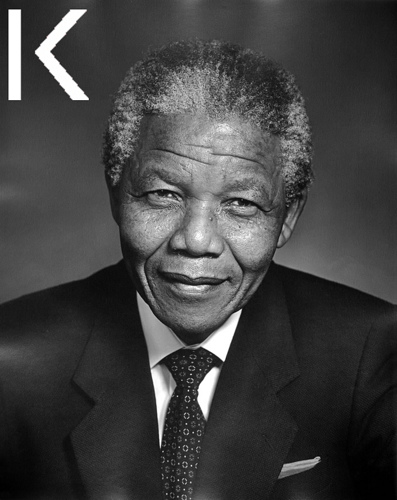

A moving scene from the movie Invictus portrays a tense conversation between President Nelson Mandela and Jason Tshabalala, his intense security chief. At issue is Mandela’s decision to employ some of the highly qualified white bodyguards trained under his predecessor during the brutal apartheid regime.

A moving scene from the movie Invictus portrays a tense conversation between President Nelson Mandela and Jason Tshabalala, his intense security chief. At issue is Mandela’s decision to employ some of the highly qualified white bodyguards trained under his predecessor during the brutal apartheid regime.

On the morning when the white men report to take up their duties with the new regime, the black guards—who had not been informed prior to this noteworthy event—react with shock and disdain. Visibly agitated, the security chief storms into the president’s office to demand an explanation. Mandela calmly makes clear his desire to be protected by a multiracial team, one that should include highly qualified members from the remnants of South Africa’s once feared apartheid security apparatus.

As such, the leader of the new South Africa had decided that blacks and whites would share the task of protecting the nation’s important public officials. And, the president, the man most in the public eye, needed to be the first to set the example. As Mandela would say to Jason Tshabalala, “the rainbow nation starts here.”

Lessons from Robben Island: Nelson Mandela entered the famous prison as an outspoken and stubborn revolutionary, considered a terrorist by the white ruling party. In the early years of his incarceration, Mandela faced endless abuse and humiliation. How does one emerge from a twenty-seven year imprisonment ready and willing to forgive those who put him there, particularly given the treatment he had received upon entry? Of course, the answer is complex, and pointing to any one aspect would be an oversimplification. To me, though, language was a crucial element at the origin of a profound personal transformation that Mandela was able to effect in his tiny jail cell.

At Robben Island, all the jailers were Afrikaners. Mandela decided to study them, mostly out of a desire to “know the enemy” in order to prevail against them, a concept he had acquired as a boxer. Early in his tenure at a prisoner, he set out to learn the language of his oppressors. He read their books and recited their poetry; he engaged prison personnel by soliciting their help in his linguistic endeavors.

By respecting his guards, by honoring their language and their traditions, the future president was able turn his personal situation around, eventually winning over his warders. In the final years, many prison officials treated Mandela as if they were his loyal friends. Christo Brand, who served as one of Mandela’s wardens for 18 years, would later tell stories of how he and others came to quietly bend the rules for their famous prisoner.

Mandela would say after his release that the prison experience taught him the power of persuasion and negotiation, tools he would use repeatedly to win over a skeptical white minority, often in their own language. He came to consider speaking the language of one’s partner or adversary as a critical element of any act of persuasion. As such, he would famously declare, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”

The example of Mandela’s learning to communicate in Afrikaans illustrates one of my themes from last week: why we should still bother to learn other languages when the whole world now seems to speak passable to reasonably good English. Of course, Mandela and the prison officials already had a language in which to communicate. However, English was nobody’s native tongue. Interacting with Afrikaners in their own language was a sign of respect, and winning their respect allowed him to come inside their world and achieve deeper levels of communication and understanding.

Already at Robben Island, Mandela was able to build exceptional bridges with his guards, bridges that won him their admiration and afforded him special treatment. Next week, we’ll see a bit more about how, years later as president, his in-depth understanding of the Afrikaners and their culture became a tool for uniting the nation.

Image: Flickr-user Festival Karsh Ottawa