In recent posts, we have seen that my business school students were far better at recalling stories and cases than they were at remembering facts, theory, or the rational discourse of lectures. At the same time that I was observing this enhanced memory effect in my classrooms, I was also finding research that explains why this might be so.

In recent posts, we have seen that my business school students were far better at recalling stories and cases than they were at remembering facts, theory, or the rational discourse of lectures. At the same time that I was observing this enhanced memory effect in my classrooms, I was also finding research that explains why this might be so.

In fact, when I searched the literature for the purposes of my doctoral thesis, I came across a number of books and academic papers that espouse a similar notion: It is through narrative constructs that human beings actually learn to think. Some neurologists even call narrative the “natural language of the brain”.

Today, many scholars believe that narrative is absolutely essential to the process of learning to think. Among these is Jerome Bruner, an eminent psychologist and prolific author from the late 20th century. Bruner wrote extensively of “the narrative construction of reality” a concept he developed from his long career studying—among other things—how we learn, both as children and as adults.

Among Mr Bruner’s conclusions is one that caught my attention, because it seemed to have a direct relationship with what was unfolding in my classrooms. Writing of children and how they learn, Bruner states: “If they don’t catch something in a narrative structure, it doesn’t get remembered very well, and it doesn’t seem to be accessible for further mulling over.”

Though the people in my classes were adults rather than children, it was clear to me that Bruner’s observations applied to the human mind in general, and that what he wrote was completely relevant to my situation. As I have written on several occasions these past weeks, what I wanted for my students was straightforward and utilitarian. Our work together will only have been successful, I reasoned, if they are able to recall our lessons later, and if they could find ways to use these learnings in their professional lives.

And so, I would like to take a closer look at Jerome Bruner’s statement in its two parts, and in the light of our recent musings on this blog. Part one: If they don’t catch something in a narrative structure, it doesn’t get remembered very well. This simply repeats something we have seen multiple times here, and a concept that I have come to believe wholeheartedly. If we want individuals to remember information for a long time, our best strategy is to present it in the form of a story.

That principle firmly established for me, it is perhaps the second aspect of Bruner’s reflection that is even more crucial, and I would like to rewrite it with a positive twist. Rather than say they will not have it accessible in their memories, let’s look at it this way: If they do grab onto something in a narrative structure, it tends to remain “accessible for further mulling over”.

What I like so much about this notion is that I think it is precisely what is happening in the situations I have described, where a former student returns to see me years after graduating and opines, “my company today is in a situation similar to the one we saw in one of the cases I recall from your course”.

How should we interpret what that student is telling me, and what the deeper significance is? To use Bruner’s terminology, the story she remembers and discusses with me is a narrative that has remained accessible in her memory. She has mulled it over, and she has noticed how and where she can use what she learned.

Using my terminology, the words change somewhat, but the underlying concept is identical. This former student has processed the virtual “experience” of studying a business case, remembered the story, and was still capable of utilizing the relevant information, even years after we studied it.

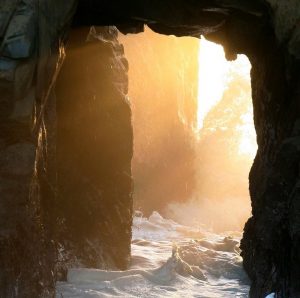

Image: Flickr user Steve Jurvetson